More than meets the eye

Jake Soros loved animals.

It started with a beloved dog named Mylady, who he rescued from a dog fighting ring. It continued with goats he cared for as part of an outreach program while he was incarcerated.

"Jake wasn't great with people, but he was so good with animals. That was where he was at his best," shares his sister, Kelly Soros. "And even when he was 35 years old and 6'3", his laugh never changed. He always giggled like he was a child."

Kelly, an emergency physician, understands her brother had challenges. A cycle of crime saw Jake in and out of correctional centres for a decade.

But he was also her brother – and she will always love him.

"Jake lived most of his adult life incarcerated, but he was so much more than that," says Kelly. "He was so proud of me for being a nurse, and then a doctor. He loved our family, especially our mom, so much. Jake just wanted to fit in. He wasn't good at school or sports, and he was bullied, so he was always trying to find where he felt good and succeeded. And, unfortunately, he was very good at crime."

Caring for patients as an Indigenous physician

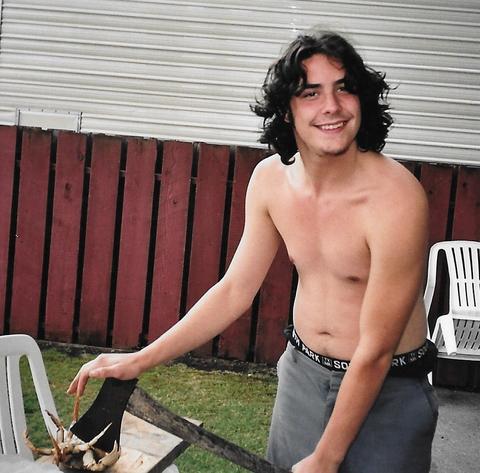

Kelly and Jake (pictured below) are Métis, descended from the Red River Settlement and Saskatchewan's Qu'Appelle Valley on their maternal grandfather's side.

Every day Kelly goes in to work in a busy emergency department in Vancouver, she draws on her understanding of structural racism and colonial policies and practices. She also applies a trauma-informed approach to every patient interaction.

"I always try to go into work seeing the world through an Indigenous lens, which sees people as more than their illness. With my lived experience, I see my patient as a full person – as a son or a daughter or a mom. I think about them being connected spiritually and being emotionally well," says Kelly.

Sadly, Jake's story ended two years ago, when he was tragically killed. However, his legacy lives on in Kelly.

She is a strong advocate for reducing stigma around incarceration, especially for Indigenous Peoples, and ensuring health care and correctional facilities are safe, supportive and culturally sensitive.

"I've never met a five-year-old who wants to be violent or use drugs," says Kelly. "You're seeing people at one point in their journey, but there are a million steps that got them to that point. I think of them as a kid who had big dreams before something happened to them. I can't change their life circumstances, but I can change how they feel when they come into my care space, which is safe and calm. I see how that can shift the tides."

"The relationship is the most important outcome for any interaction."

– Kelly Soros

Sharing Jake's legacy in hopes of creating change

To share her experience to benefit others and create change, Kelly got involved with BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services (BCMHSUS) as a family partner.

"Being a loved one of someone in jail is a really hard journey for a lot of reasons. I would spend months looking for Jake because I didn't know where he was or if he was alive, and then I'd find him in the Prince George jail," shares Kelly. "When Jake was alive, I wish I was a bit more graceful with my love for him. You can love somebody while having firm boundaries and not condoning their behaviour. I saw how powerful it was for Jake to have our mom in his corner, no matter what."

Kelly is featured in a family partner video series, which bring viewers along on a journey into the stories of family members of people with lived and living experience of mental health complexities, substance use issues and criminalization.

Led by the Patient Experience and Community Engagement team at BCMHSUS, the videos were created in collaboration with a project team of student designers, faculty, and staff from the Health Design Lab at Emily Carr University of Art + Design.

World premiere of family partner videos

The family partner video series officially debuted at a screening at Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver on June 5. The public were invited to attend.

After the screening, a panel discussion was held with the storytellers, including Kelly.

"For people working in health care or in the prisons, we have to remember that these patients and inmates have families who love them. We want them to get better and get back to their family and not cause any more trauma," says Kelly.

The videos are part of Understanding Each Other Together (UNITE), a broader initiative aimed at disrupting stigma and advancing person-centered care.